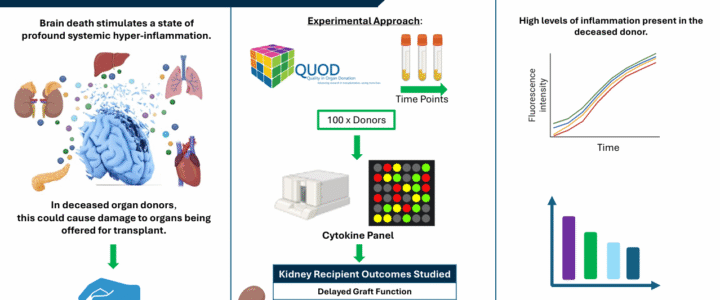

The process of death invokes a complex set of events leading to profound hyper-inflammation. Systemic hyper-inflammation is a well-established cause of organ dysfunction, evidenced by the multi-organ failure observed in sepsis. It is reasonable to infer that in deceased organ donors, death-induced hyper-inflammation could have significant consequences for organs being offered for transplant.

A study being carried out by PhD student Annie Mae Goncalves-Bullock and led by Dr Nina Dempsey and Prof Ascanio Tridente at Manchester Metropolitan University and Mersey & West Lancashire NHS Trust, is currently using QUOD blood samples from kidney donors to investigate the importance of donor inflammation on outcomes in kidney recipients.

There is already significant interest regarding the effects of inflammation on pre-donation organ viability, and the consequences for short- and long-term outcomes. Deceased donor management guidelines recommend high-dose corticosteroid therapy is administered to the donor as soon as possible after donor identification and confirmation of death. Corticosteroids are used in this manner to blunt the inflammatory cascade, stabilise donor physiology and increase organ utilisation. However, there is concern that the non-specific nature of corticosteroids means that inflammation persists in deceased donors and there may be significant room for improvement of protocols. A deeper understanding of the drivers of the immunological events that follow death is essential for the development of future donor management protocols.

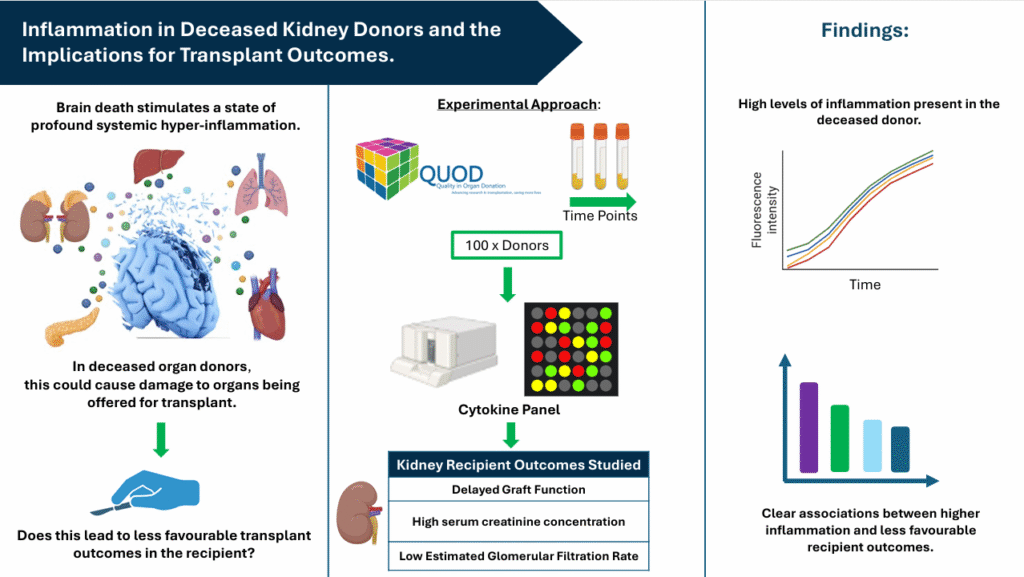

The group is therefore measuring a wide panel of cytokines at three time-points during the donor management period (DMP) and working to establish their independent association with short- and long-term kidney transplant outcomes. Given the wealth of donor and recipient data QUOD can provide alongside samples taken across the course of the DMP, the group feels that the QUOD biobank is the perfect resource for answering such questions. The group has chosen to focus on the outcomes of kidney transplants since the kidneys are usually the first organ to fail in response to the renal medullary hypoxia and systemic inflammation present in sepsis, prompting the hypothesis that this would also be the case following death.

The donor sampling time points being considered are termed DB1 (shortly after donor identification and consent, allowing for capture of baseline inflammation), DB3 (at time of preparation for kidney retrieval, allowing for capture of biological changes from clinical interventions) and DB4 (at the time of organ retrieval, reflecting the donor’s condition at the final stage of the DMP). The primary outcome is delayed graft function (DGF), defined as need for dialysis within 7 days post-transplant. Other outcomes being investigated are high serum creatinine concentrations and low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 3- and 12-months post-transplant.

Despite standard DM protocols being used in these donors, the group is already seeing high levels of inflammatory markers persisting in these donor samples. It is hoped that the data from the study will support the growing evidence for revised immunomodulation protocols in deceased donors that are more targeted towards the initiators of the inflammatory cascade.

The PhD studentship is jointly funded by Manchester Metropolitan University and the NHSBT Organ Donation Fund.

Interim results from this study have recently been presented by the group at the British Transplantation Society conference, Brighton, March 2025 and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) conference, Munich, October 2025.